Alex Ross and the Future of Classical Music

(in three parts. Part II | Part III )

Alex Ross was irritated by the 2018 celebration of Leonard Bernstein’s 100th birthday at Tanglewood and throughout the world. In his article “Leonard Bernstein and the Perils of Hero Worship“, he flinches at every superlative about the first great American-born conductor. The celebrations “have touted the man as a kind of musical superhero,” perhaps erroneously? “At a time when classical music was retreating to the edges of the cultural landscape, Bernstein appeared to reverse the process almost single-handedly, through force of will” — appeared to. Tanglewood’s celebration was a “respectful pageant in honor of a legend from another time” who now “recedes into history”. With a loosely thrown together list of historical circumstances, Ross appears quite seriously to argue that Leonard Bernstein was, more than anything else, at the right place at the right time. “His charisma was indeed potent,” Ross writes, but we have all been fooled. Behind that thin facade, it was The New Deal, the Cold War, McCarthyism, and myriad other coincidences propping up Bernstein’s talents, success, and lasting impact.

Somebody made Alex Ross sit through Bernstein’s Candide at Tanglewood, not his favorite piece by a composer about whom he already has clear reservations. He would rather have heard Mass, which lights Ross’s fire by “giving voice to the composer’s radical politics.”[1]In fact Mass contains hardly a word about politics but is rather a piece about faith. Candide is Bernstein’s most political theatre work but is by no means radical. Ross does not appreciate Candide‘s “sassy dissonances” and “pert tunes”, and to top it all off, “its ethnic stereotyping and its rape jokes give pause.”

Ethnic stereotyping? Rape jokes? Pert tunes! We can’t have those. Not in comic operetta, not in Voltaire, not anywhere. One can picture Mr. Ross wound taught with sensitivity, sitting in his complimentary seat in the Koussevitzky Music Shed, “pausing.”

Imagine had Bernstein himself walked up and patted Mr. Ross right in the crotch. That is just one of several Bernstein mannerisms detailed by recent memoirists to whose “disconcerting” work Ross devotes a paragraph. Other offenses included flicking cigarettes and calling people “fuckface.” It is a good thing Ross was not a critic back in Bernstein’s Tanglewood of the 1980s, or he would surely have run screaming into the Berkshires in terror. “There will not be another [Bernstein],” Ross mansplains, “not because talent is lacking but because the culture that fostered him is gone.”

Polymath / polyglot / composer / conductor / pianist / teacher / author / humanitarians are falling unnoticed from the ceilings everywhere, Ross wants us to believe. The problem is our culture does not “foster” them. But that does not matter: “The future of classical music cannot consist in waiting for another telegenic superstar,” reads the subtitle, as though every family is still gathered around the console TV set waiting for “Great Performances” to come on.

If his rambling tract seems not to have a point, that’s because it doesn’t. Ross is merely portraying himself as fashionably averse to a great musician of the past, in particular, one who was white, Jewish, and male.

Later in 2018, in “Classical Music’s Chief Visionary Goes West Again,” Ross covered Esa-Pekka Salonen for at least the eighth time. Trying to sound like one of the boys, Ross coolly relates his trip to Santa Monica to visit personally with Salonen, who, sitting underneath a cactus tree with an espresso, in turn relates his “dinner with Michael [Tilson Thomas] the other night,” during which they had joked about who had taken over whose job when, and so on. Other topics include Salonen’s ad for the Apple iPad in 2014 and his connection to a Silicon Valley venture capitalist who sits on the San Francisco Symphony’s board of directors.

Uh-oh. This is the unmistakeable bro’s club of white, moneyed power that in a few short years will have the entire orchestra business in America backpedaling furiously, or at least trying to appear to do so

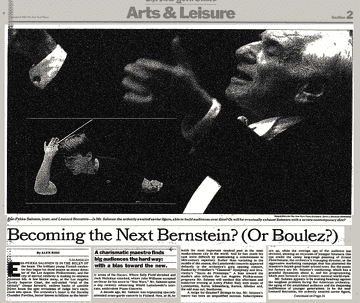

In a chain of self-citations, Ross traces his adulation of Salonen back to a first interview in 1994, in The New York Times. This was before Ross’s job at The New Yorker, at a time when the music world was still raw with the loss of Leonard Bernstein. Much to the inconvenience of his future self, he incautiously titled the article “Becoming the Next Bernstein (or Boulez?)“. Note the question mark is inside the parentheses — it was not a question of whether, but which, conductor Salonen would become the “next” of. “Is he the next Leonard Bernstein, the ardently awaited savior figure, able to explain the unfamiliar and build audiences over time?”, Ross asks.

If so, some poor critic in 2058 will have to sit through Salonen’s birth centenary celebration. Assuming Salonen, like Bernstein, will be dead and defenseless at his own event, will that critic dethrone Salonen with mixed assessments and ambivalent sympathies? What references in Salonen’s compositions will be offensive in retrospect, what aspects of his behavior will be distasteful, what other transgressions will have been detailed in ghastly memoirs by family members and associates?

None, because this is all a pack of nonsense. Already by 2018, Ross has given up waiting for the “savior” to materialize out of Esa-Pekka Salonen.

But no one asked Alex Ross to find the next Leonard Bernstein or even promised there would or should be one. He did that to himself. If Esa-Pekka Salonen ultimately disappointed, what then is the “future of classical music,” according to Ross? Was that just a platitude to anchor his ding against Bernstein? Or is he really searching for an answer?

> Part II: “Searching for Alternatives to Esa-Pekka Salonen”

References

| ↑1 | In fact Mass contains hardly a word about politics but is rather a piece about faith. Candide is Bernstein’s most political theatre work but is by no means radical. |

|---|