5. Critical Critical Theory Theory

Being Part 5 of Philip Ewell Go Down In History

(updated September 2025)

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 6

“If music theory is so flawed, what would you have us replace it with?” – Basic Trope of The White Racial Frame and White Privilege, Philip Ewell, “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame”, section 7.2

Contents

-

- Message Received

- Critical Theory’s “White Racial Frame”?

- Critical Critical Theory Theory

- Misappropriation, Misattribution and “Knowledge Power”

- Erving Goffman and Frame Analysis

- Joe Feagin’s The White Racial Frame: Summary

- Joe Feagin’s The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Framing and Counterframing: A Reframing

- Secret Monitoring

- Racism Pseudoscience

- Stressful Persuasion

- Ideology

- The Authority of Lived Experience

- “Contextualization” and Narrative Control Power

- Exclusive Inclusivity

- Communication, Metacommunication, and Frame Entrapment

- Gregory Bateson and the Double Bind

- Frame Trapping Critical Theory

- Correctives

- Recommended Reading

Message Received

In Part One, I stated I would offer some means to speak or act meaningfully in response to Critical Theory. These are to be offered in Part Six. However, long consideration has made clear that the most important transformation occurs on exactly that level from which Critical Theory discourages attention: the individual.

The indictments Critical Race Theory makes against not only whites and males, but against all persons who participate in the “white racial frame”, are many and severe. That it directs them abstractly to “whiteness” and “maleness”, rather than actual persons, is in fact a tactical subterfuge to be examined in this section; it is meanwhile pointed out that doing so does nothing to reduce the devaluation many individuals experience, whether because they are white, male, or both, or because they are otherwise unsupportive of Critical Theory’s agendas. Though the Critical Theory tactic targets groups, it is to the individual that psychological cost occurs. Not only can that cost be both severe and isolating, as discussed in Part Four, but once psychological encroachment begins, Critical Theory may seem a nearly permanent aspect of all exerience, due to its universal mandate to undertake “gendering” or “racializing” work and self examination that is, for all practical purposes, unending. In his book “The White Racial Frame,” to be discussed at length in this section, Joe Feagin suggests it will take many people “an entire lifetime” to come to terms with their own racism.

Such demands pose a unique problem for musicians and artists, since artists’ most valuable asset is time. Intrusive and infinite thought patterns pose an exisential threat to the imagination and to artistic study and work. It is a sufficiently serious problem to address independently of the group level, even if Theory wishes to distract us from it.

We begin then by rejecting the twin abstractions “whiteness” and “maleness” and establish that, though Critical Theory may address people in groups, it can yet be responded to individually. From there, we add that the message is loudly and clearly heard: The indictments Critical Race Theory makes against whites, males, and all of those who participate in the “white racial frame” — which, as this section shall show, is all persons — are many and severe. The accountability it places upon them is heavy and grave. This section, with Part Six, responds with commensurate rigor and austerity, with the objective to restore stability, clarity, and independence of thought to those troubled by the riddle of Critical Theory in academia or elsewhere, so that work considered meaningful to each individual may be continued.

Critical Theory’s “White Racial Frame”?

It is easy to forget that ideas, such as framing, equality, human rights, or systems theory, upon which claims of systemic oppression rely, did not arise with nature. They had to be thought up, developed, disseminated, applied and tested over generations or centuries, often at tremendous cost in life or livelihood. The ideas that survive across place and time are an unearned inheritance, a collective knowledge body to which each person has access according to the period of his or her own lifetime.

When a particular idea comes into common use within a field or in society at large, it may be felt, in a sense, to be “public domain”, something everyone is entitled to use, change, or rewrite for any purpose without responsibility or accountability. However, the best and most useful ideas were attained at great effort and discipline, a cost that we, their beneficiaries, do not fully share. One result is that ideas may adopted and wielded with far less effort or discipline than necessary to fully understand their depth or power. Another is that ideas of the past may be easily misappropriated or reformulated, then presented or mistaken as original, either by deliberate deception or through unawareness.

Critical Theory presents itself here with a unique dilemma that I will now begin to unpack.

Nowhere in his citation chains does Philip Ewell reference the intellectual roots of Critical Race Theory. In the fifth part of his noted blog post, he cities Sara Ahmed, who “adopts a simple citation policy: she does not cite any white men” (emphasis mine). Possibly, this and similar attitudes have permitted the belief that Critical Race Theory is original, that scholars such as Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, Cheryl Harris, and those they all cite in turn, invented it from first principles. Since advanced academic degrees can now be earned without learning the history of Western thought, it is also possible many are not aware Critical Theory relies on at least two centuries’ prior work.

Dr. Derrick Bell was a Harvard professor of law who wrote the first texts now known as Critical Race Theory and coined the term “Critical Race Theory”. In fact, Bell coined only the middle word, “Race” inserting it between the two words of an earlier field, Critical Theory. Critical Theory originated in Germany in 1933 and is occasionally misunderstood, due to having originated the name, to have had close ideological alignment with Critical Race Theory.

In fact, American Critical Race Theory of the 1970s was most closely related to a field called Critical Legal Studies that enjoyed popularity both in academia and the practice of law in America and Britain during the 1960s and 1970s. Critical Legal Studies advanced that the law serves hidden interests of the dominant class with the purpose to “maintain the status quo”, wording of which Philip Ewell is fond. Critical Legal Studies, however, cannot be credited with originating that idea, rather only with its application to law.

The generation that populated Critical Legal Studies had lived through the two decades encompassing the American Civil Rights movement, the women’s rights movement, numerous other youth political movements, and the gradual disillusionment with American leadership and politics that culminated in the Vietnam War and its aftermath. Though Critical Legal Studies owes much in turn to another American predecessor, Legal Realism, its lineage until 1970 is mostly in European thought:

Disenchanted with America, Critical Legal Studies scholars turned to several non-American sources, Marxism and Deconstructionism being the most prominent. At that time, the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels — together, “Marxism” — were over a century old and had spawned several national revolutions and played a role in two world wars. Deconstructionism was a younger field entering its second generation. Jacques Derrida, who rejected the term “deconstructionism” while being yet its most prominent figure, originated much of the language that would later, in English translation, find appropriation into Critical Race Theory: “close reading,” “grand narratives,” “questioning assumptions,” “dominant discourses,” the special use of the term “text”, and so on. The philosopher Michel Foucault originated much of Critical Race Theory’s repertory of language and method to examine and expose mechanisms of social control and the ideas of “knowledge power” and “problematizing.”

Preceding Deconstructionism by a few decades was the Frankfurt School at the Institut for Social Research at Goethe University in Germany. Its founding philosophers originated the field “Critical Theory.” They included Erich Fromm, Max Horkheimer, Otto Kirchheimer, Walter Benjamin, Jürgen Habermas and Theodor Adorno. It happens that Adorno, usually considered the founder and principle thinker of Frankfurt Critical Theory, was a pianist and musicologist.

If the Critical Race Theory literature in America is vast and dense, the Frankfurt School dwarfs it in complexity and unapproachability, especially to non German-speakers. To form just an overview requires some understanding of the philosophy of Kant and Schopenhauer, the philosophical and economic writings of Karl Marx, the many causes of the First World War, and finally the social and political conditions of Weimar Germany that contributed to the exploitation of the working class. It can hardly be supposed more than a small number of persons in the world possess sufficient understanding of this history to assess the soundness of its eventual application to the problems of a time and society unknown to its authors.

The Frankfurt School would not have anticipated Critical Race Theory might one day undermine its own origins by imputing the European culture in which it germinated as race-exclusionary and white supremacist. Rather, the Frankfurt School was concerned with class. Their goal was the “total liberation from ideologies” via critique of social and political power structures — that is, by examining how and where power is located and operates. DEI and antiracism as understood in contemporary America were not what they had in mind. Frankfurt Critical Theory was interested in conveying their understanding to a small population of sufficiently capable intellects. This is borne out by the conspicuous oblivion of most identity-oriented American Critical Theorists to any of these intellectual antecedents, not to mention the contradictions in their applications of them.

Theodor Adorno focused in particular on the impact of capitalism upon the public audience for music and, in turn, upon the composers who wrote for that audience, whom he viewed with scorn. His Philosophy of New Music advocates an aesthetic elitism in which the few composers able to comprehend (Frankfurt) Critical Theory, working in deliberate isolation from public recognition or material reward, pushed musical progress toward “truth,” Adorno’s exact definition of which can be difficult to discern. This, Adorno believed, was possible only by rejecting tonal systems of the past and adopting studied disinterest in public demands of any sort. To the extent that Adorno’s Critical Theory was concerned with liberation at all, it was for a small number of academic composers, from the base expectations of a mass public degraded by capitalist commodification. When speaking of liberation, then, the Frankfurt School meant liberation from the public, not for the public. Adorno volunteers that his is an elitist philosophy, reserved for a select few, their primary audience being one another, to the explicit exclusion of those who could not comprehend. By the time Adorno wrote The Authoritarian Personality in 1949, Critical Theory itself already bore many features of an authoritarian ideology.

Frankfurt Critical Theory was, like the fields mentioned above, a response to the perceived failure of several previous economic, social and political philosophies. It aligned to some extent with Marxism, though it criticized certain applications of it. It was more heavily indebted to the philosophies of Hegel and Heidegger, who in turn were responding with varying degrees of dissent to German Idealism.

This sprawling lineage of thought presents no unified front. Debate among and within groups, fields and subfields could be acrimonious, with schism playing a large role in the rapid multiplication of specialized sub-branches and movements: intersectionality, Legal Positivism, Pragmatism, Postcolonial Theory, Poststructuralism, Critical Geography, Anarchism, Decolonial Theory, each successive wave of feminism, the cross-purposes of various schisms within the Civil Rights movement culminating in the Black Power movement, and more recently, Critical Disability Studies, Queer Theory, Environmental Justice, and so on.

As a general if oversimplified summary, each group or field arose in response to the shortfall of one or more of the previous, in a cycle of theory, then application, leading at times to revolution or temporary improvement, and finally some form of disorder or catastrophe. By the time each theory achieved application, events had made them inadequate, leading to the need for new theory. To borrow from one of the few fields to recognize this problem, cybernetics, each theory was “one hundred percent prepared for yesterday.”

Humility before this enormous historical cycle might at times have been a good proposal before placing faith in new theory. But the perceived urgency to act on problems of the moment usually prevented any notice that the theory-praxis loop was in most cases unpredictable. This surfaces in the destabilizing actions of Critical Theorists, such as in Philip Ewell’s certainty that “everyone benefits,” and his flippant admission, on the other hand, that “where we will end up, I do not know.”

That Adorno’s intellectual starting points in Frankfurt Critical Theory, to take just one example, were also the antecedents for the contemporary vision of forced inclusion policies in academic music, such as advocated in Philip Ewell’s 2019 plenary paper, is an awesomely preposterous historical spectacle. To be exact, it is not the soundness of any particular worldview, but the demonstration that from Critical Theory can be deduced such mutually irreconcilable worldviews, that betrays its fundamental indifference to any moral, artistic or political principle. Tremendous respect to the power of redefinition is due when words such as “liberation”, “ideology” and “progress” may be used in service of mutually exclusive ends.

It also demonstrates Critical Theory’s applicability to virtually any interests or ends; far removed by now from its original environment and purposes, the language and tools accumulated from Critical Theory and all its related thinkers furnish a value-agnostic means to deconstruct or intimidate, any set of beliefs or values that happen to prevail, according to and limited only by the interests of the practitioner. Critical Theory enacts, by inversion, the system from which it sought liberation, replacing one authority with another: itself.

If one chooses to focus on race and gender, as Philip Ewell does, American Critical Theory, including Critical Race Theory and all forms of intersectional Theory, is a synthesis of mostly white, mostly male, and mostly European thought. That some may read that fact with outrage or disbelief demonstrates how thoroughly Critical Theory, by appropriation and selective citation, has erased all vestiges of its ideological debt to the history it condemns.

Once recognized as a branch of Western thought, even if unacknowledged, Critical Race Theory can be understood as a series of iterations on applied science and philosophy, each iteration succeeded by then next when found to be insufficient.

“If music theory is so flawed, what would you have us replace it with?”, asks one of the white male framed tropes Ewell caricatures in his 2019 plenary paper. In imaginary response Ewell writes, “This is a deceptive tactic. By switching immediately to a discussion of alternatives, the white frame seeks to change the subject. First there must be a reckoning with respect to the white racial frame, and a rigorous analysis of its effects. Further, no one person should be responsible to offer an alternative to centuries of white racial framing.”

The replacement hides in plain sight: it is Critical Theory.

Critical Critical Theory Theory

Critical Theory has long ossified from its origins at the fringes of Weimar thought into a feature of much American society and many institutions. To all the chaotic events of Part 2, and the destabilizing emotions of Part 4, may now be posed a simple and possibly obvious reframing: Critical Theory is an instance of that which it investigates; Critical Theory is a power structure. It is clear the objective of Critical Theorists is not only to dismantle existing power, but to transfer and exercise that power to its own interests.

If Critical Race Theory is Critical Theory applied to race, Critical Critical Theory Theory, is proposed as Critical Theory applied to Critical Theory. Critical Theory employs the same coercive tactics as most power systems, and in doing so, participates in all the behaviors it finds objectionable. That it easily convinces many people otherwise is attributable to its contrary language claims that it seeks radical equity and inclusivity. These will be dealt with shortly. In the meantime, it is sufficient to state that power imbalance is an often problematic aspect of all systems.

How does Critical Theory exercise power? Many examples from Philip Ewell’s work have been covered: threats, force, fear, language control, blackwashing, intimidation, creating confusion, suspicion and distrust, framing dissent as proof, keeping the focus on race, and so on.

But Critical Theory’s power is still deeper and more complex. Utilizing Critical Theory’s own practices of “close reading” and “problematizing”, appropriated from Michel Foucault as described above, as well as framing and other tools, many more subtle and complex mechanisms of its power become clear.

Misappropriation, Misattribution and “Knowledge Power”

Michel Foucault’s idea of “knowledge power” refers to the possibility that those who control knowledge have the power to influence societal norms, behaviors, and beliefs. Knowledge, however, is not the same as understanding. Incomplete or incorrect knowledge, when presented with the appearance of authority, is no less capable of power and influence.

Philip Ewell derived “Music Theory’s White Racial Frame” from Texas A&M University sociologist Joe Feagin’s book The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Framing and Counterframing. To his credit, Ewell provides attribution to Joe Feagin both in his plenary paper and in his Zoom talks.

Unlike Ewell, Joe Feagin does not provide clear attribution. Although Feagin coined the “white racial frame”, he did so, like Derrick Bell, out of an extant concept. He writes, “Several contemporary sciences — especially the cognitive, neurological, and social sciences — have made use of the perspectival frame that gets imbedded into individual minds (brains), as well as collective memories and histories, and helps people make sense of their everyday situations.” Here is an example of the assumption, described earlier, that an idea can be “made use of” without credit to its origin or accountability to its full content.

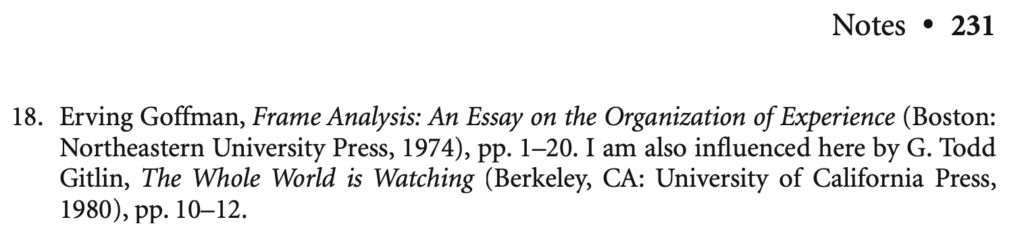

Framing, like Critical Theory, has a history independent of race scholarship upon which sociology has been built decades of common practice. Only once Feagin does cite its source, in a footnote, and only to pages 1 – 20:

Race scholarship relies so heavily on Western intellectual tools such as framing that its silence on their origins, and its selective avoidance of their complexities, while not exactly plagiaristic, amount to highly problematic misappropriation and, at times, errant outcomes caused by unskillful reading and interpretation. Feagin’s book, and by extension Ewell’s work, are examples of misappropriated knowledge power.

Insight into Ewell’s work may be gained by examining its antecedent in Feagin’s. With a PhD from Harvard University (1966), Feagin is a contributor and beneficiary of the American academic establishment and as such, possesses the senior, tenured academic power that Philip Ewell critiques in his lectures, talks and plenary paper. Feagin’s failure to adequately credit and explain framing, or to include its many complex and subtle implications upon his work, calls into question his credibility and at times his competence.

Erving Goffman and Frame Analysis

The Jewish Canadian-American sociologist, psychologist and anthropologist Erving Goffman authored several books concerning framing, beginning with The Presentation of Self in Daily Life (1959). Goffman fully codified and introduced framing to mainstream academia and the public in his 1974 book Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. In his introduction, Goffman credits numerous previous thinkers. “I have borrowed extensively from all these sources, claiming really only the bringing of them together,” he writes. Among those he credits in the full text his introduction are William James, Alfred Shutz, Harold Garfinkel, Luigi Pirandello, John Austin, Ludwig Wittgenstein, D.S. Swchayder, Barney Glaser, Anselm Strauss, William T. Cone and Jacob Brackman.

Goffman singles out one particular thinker to whom the origin of “framing” is owed: Gregory Bateson (1904-1980). The first known use of “frame” in Goffman’s sense, the one Feagin cites, can be found in Bateson’s article “A Theory Of Play and Fantasy,” in the American Psychiatric Association Psychiatric Research Reports, volume II, 1955. It was reprinted in his Steps To An Ecology of Mind (1972).

It will be helpful to explain framing, since Joe Feagin does not. A frame is a way to organize experience around parameters that provide specific meaning and generate, in turn, rules or expectations for communication and involvement in a particular activity. In Goffman’s words, a frame tells us “what is going.”

“…[E]ach primary framework allows its user to locate perceive, identify, and label a seemingly infinite number of concrete occurrences defined in its terms. He is likely to be unaware of such organized features as the framework has and unable to describe the framework with any completeness if asked, yet these handicaps are no bar to his easily and fully applying it.”

Goffman’s twenty page introduction illustrates one feature of framing: it is reflexive — every frame can be framed, a move he calls a “transformation.” On page sixteen he writes, “That is the introduction.” Then he comments that introductions frame books’ contents. Then, he asks what role commenting on the role of introductions plays, wondering if doing so influences the reader’s own framing of the book. Then, he wonders whether raising that question “excuses” having raised the previous. Each of six further sections frames the previous, frame around frame, ending with a single sentence that frames the rest: “That is what frame analysis is about.”

Possibly, the reason Feagin cites only pages 1 – 20 is that pages 21 – 576 make clear frame analysis opens his work to numerous vulnerabilities, to the extent one wonders if he has even read them. It is helpful, however, to know the analytical tools Feagin believes himself to understand.

Equally important is to understood what framing is not. Framing does not read into the minds of others or claim ultimate interpretation of mass behavior or total reality. “Framing does not so much place restrictions on interpretations but open them to variability,” Goffman writes. Framing is not about “depending on or harking back to some prior or ‘original’ interpretation.” Frames have no agency, cannot speak or act on their own, and there is no evidence they are “imbedded into individual minds (brains)”, as Joe Feagin writes, in any sense corresponding to medical, scientific or other empirical understanding. Goffman even expresses doubt about the range of framing’s applicability and states framing mostly concerns, at least in his own book, “the structure of individual experience.” Matters of sociology, he writes, “can be dealt with quite nicely without.” If framing were “dependent on a closed, finite set of a rules,” he writes, it would be the “sociologists alchemy.”

But it is not. Framing is rather a way to make sense of perception. “What is going on” may be many simultaneous things, with multiple levels of meaning, which Goffman calls “tracks.” To assume a frame is to select among many, possibly infinite, ways to organize experience. All frames are subject to multiple modes of transformation for which Goffman has specific terms: “keying”, “fabrication”, “anchoring”, and so on.

Goffman’s frame transformations are equally applicable to counterframe the “white racial frame” and its numerous “subframes” and “counterframes” that Feagin believes are imbedded in the brains the white American population. Though Feagin’s and Ewell’s use of “counterframing,” “reframing,” and “deframing” are not among the transformations Goffman offers, they can be mapped approximately to those he does.

Joe Feagin’s The White Racial Frame: Summary

There is something distorted about the white psyche. — Joe Feagin

Though Joe Feagin summarizes early what he means by “the white racial frame”, he supplements it as the book progresses, until the term finally carries the aggregate weight of an excoriating and unremitting invective. The challenge in summarizing it is not to remain impartial but, to the contrary, to avoid mischaracterizing its severity by omission or understatement.

Feagin characterizes the white American population as basically uniform and undistinguishable, referring mostly to “whites as a group.” No important distinction appears in his book between “ordinary” or “rank-and-file” whites, as he calls them, and “elite” whites, neo-Nazi organizations, far-right extremists, nationalistic or authoritarian groups, or “skinheads.” Feagin posits a “white character structure” which has the white racial frame “deeply embedded in the neuronal structure through repetition.” This is partly because white persons, Feagin says, tend to have homogenous networks that encourage conformity, groupthink, and grouped behavior or “narratives.” These mostly concern conquest, superiority, hard work, achievements, and the desire for dominance over others. “Whites and whiteness are generally viewed in positively framed terms by most people who consider themselves white.” At various points throughout the book, Feagin refers to white persons as ignorant, arrogant, greedy, predatory, underdeveloped, hypocritical, and preoccupied with prestige, conformity, sexual jealousies, impulses, habits, superiority, pride, joy in being white, hostility, and other “miscellaneous wants.”

Furthermore, white persons have deep negative feelings about Americans of color that involve racial stereotypes, prejudices, conceptual ideologies, interlinked interpretations and visual images that see black people as beastlike, cruel, hateful, deceitful, ugly, lazy, animalistic, ape-like, ignorant, criminal, devil-like, unintelligent, and as “natural slaves.” These negative views are not restricted to blacks but encompass “numerous anti-others subframes” transmitted and sustained by a hidden racial curriculum. White persons believe Asians “don’t speak well”, “have accents” and are submissive, sneaky, stingy, and greedy. To Native Americans, the white racial frame has “grouped diverse societies together” as savage, treacherous, unreasonable, brutish, heathen, barbarian, irrational, unvirtuous, merciless “wild beasts”, inconstant in everything. Towards Hispanics, whites take part in Spanish “language mocking” with joking terms such as “no problemo,” “el cheapo,” “watcho your backo,” and so on. “Even Jewish Americans are made fun of,” Feagin writes. All these stereotyped views and their corresponding behaviors lead to guilt, shame, rationalization, disgust and fear.

As an aspect of the “white racial frame”, white persons hide all the above under a linguistic veneer of colorblind rhetoric, asserting their own virtuousness while projecting their personal fears, often rooted in childhood, onto black and other non-white persons. Many whites have undergone a “massive breakdown of positive emotions” for people outside their “group.” White people see no need to learn much about other countries and peoples, are arrogant about the superiority of U.S. institutions, and generally believe what is untrue. In support of his assessment, Feagin cites other writers who referred to “materialistic greed, lack of spiritualism, human insensitivity”, and referred to white people as “nothing but liars.” With the American lawyer and United States judge Hernán Vera, Feagin has coined the term “social alexithymia” to describe the “commonplace inability of whites to comprehend and relate to the great pain and destructiveness of the racist experiences endured by Americans of color.”

Joe Feagin’s The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Framing and Counterframining: A Reframing

To pose the fundamental question of frame analysis, “what is going on” in Joe Feagin’s work?

Though Feagin does not use precisely the language of frame analysis, he wishes to persuade readers that the “white racial frame” is an example of what Erving Goffman calls “frame fabrication” — an intentional effort to deal with activity towards a particular dominant understanding. Specifically, Feagin wishes to say that “the white racial frame” was designed throughout history and sustained in the present by white people in order to dominate other races. Frame fabrications are part of what Goffman calls the “manufacture of negative experience.” The purpose of manufacturing negative experience is to cause others to question “what is going on.” The dominated person or group, in this case non-white people, are then referred to as “contained” by the frame.

Fabrications, Erving Goffman writes,

are subject to a special kind of discrediting. When the contained party discovers what is up, what was real for him a moment ago is now seen as a deception and is totally destroyed. It collapses. Here ‘real,’ as [William] James suggested, consists of that understanding of what is going on that drives out, that ‘dominates,’ all other understandings.

Feagin’s objective is to accomplish this “discrediting” and reveal “the white racial frame” as a deception, a manufacture of negative experience by whites to contain other races.

But Feagin’s most powerful framing is, as Goffman tells us, the one of which he is not entirely aware: his attempt at discrediting is also a frame, to which all the same transformations are applicable. Since this “outer lamination” of white people concerns in turn their negative framing of others, as summarized above, his reframing is a manufacture of negative experience and can also be framed as a fabrication. Simply put, Feagin’s outermost frame is a negative stereotyping of white people.

It might be suggested that Stanley L. Barnes, like Joe Feagin, is unaware of his own framing and that this article is also subject to negative framing. This is correct. However, each frame transformation comes at a cost to clarity and understanding. As transformations pile upon one another, confusion compounds. “After a certain number of turnings, no one can trust anyone,” Goffman writes. This was illustrated by the events in Part 2 and Part 4. Eventually, all statements are subjectively contingent and any hope of exact meaning is obfuscated entirely. It has already been discussed that to destabilize and induce general confusion is a design feature of Critical Theory.

By applying further frame transformations, it becomes clear however that the outermost frame finally exhibits all the same problems as the inner: That white people stereotype other races itself becomes a stereotype. In The White Racial Frame, Joe Feagin claims that this negative framing of whites is no stereotype at all, but is true. This raises the question whether the contained stereotypes, those of other races, are also true. Here is a main reason many people, not only white people, are uncomfortable discussing racial and other stereotypes: to debate the truth of negative stereotypes raises uncomfortable possibilities for all people subject to negative stereotyping and easily approaches, as Philip Ewell says, debating one’s “own humanity.”

Since it is now clear framing is an outgrowth of Western thought dependent predominantly on the thought of white male thinkers, it can even be suggested case that to utilize it at all is to engage in the “white framing” both Feagin and Ewell find problematic.

It is neither important nor helpful to criticize Joe Feagin for overlooking all of this; had he known better, he would have avoided the inner frame in the first place, seeing it to be easily rendered problematic by further transformation. Feagin merely is unaware of his own framing, as he claims most white people are, and as Goffman says all people are. Feagin’s work amounts to a misappropriation and misapplication of frame analysis.

However, this oversight can usefully be extended to reveal the scope of framing’s own persuasive knowledge power through the manufacture of negative experience. In his “outermost lamination”, Feagin claims to know inside the minds of white people collectively, for example. Though frame analysis is not capable of that, it is capable of persuading that it is. Due to its power to induce a particular dominant idea of “what is going on”, framing is capable of both exercising and legitimizing control over individual thoughts and beliefs. In the same way Feagin claims white people have attained that power over other races, to discredit “the white racial frame” is persuasively powerful. Any individual who feels himself or herself racially oppressed, or is empathetic to those who do, may find immediate relief in the idea that it is all explainable as an elaborate deception that simply needs reframing or, to use the misappropriated antiracist term, “deframing”.

Goffman writes that doing so is a self-reinforcing activity, as it tends to increase the framer’s confidence in his or her own framing or “deframing” and lead to misguided belief, or “insider’s folly.”

When an construction is discredited — whether by discovery, confession, or informing — and a frame apparently cleared, the plight of the discovered persons tends to be accepted with little reservation, very often with less reservation than was sustained in regard to the initial frame itself. And this acceptance tends to be given by all parties to the uncovering, the duped, the dupers and the informants. It also seems that when an individual becomes involved in framing others, his critical reservation to the venture itself and to his coconspirators is appreciably reduced. In regard, then, both to clearing frames and in fabricating false ones, there will be a special basis for firm belief in what it is that is going on. This being so, there is a special way of inducing misguided belief. This is insider’s folly.

“Discovery“, “confession“, and “informing” may seem hyperbolic terms to cite here from Goffman.

Secret Monitoring

Among the most disquieting aspects of Joe Feagin’s work is an overt disregard for civil privacy. In a practice he terms “recording exercises,” the findings of which he revisits over and over, Feagin enlisted hundreds of students and other participants on numerous occasions to keep “diaries” of racial conversations and encounters in public and private life. More plainly stated, Feagin organized others to monitor and document the words and behavior of their friends, relatives, associates and strangers without knowledge or consent and to provide these in writing to Feagin for his research.

The American Sociological Society, of which Joe Feagin has been president, has a code of ethics restricting observation in any “private context where an individual can reasonably expect that no observation or reporting is taking place” in addition to explicit requirements for research on children. This poses a problem for Feagin’s research: he writes, “as whites get older most learn better how to hide certain racial attitudes in public (frontstage) settings, such as with researchers, pollsters, or other strangers, and to reserve most overly racist commentary for the private (backstage) settings with white friends and relatives.” For this reason, secret monitoring of backstage — private — settings was necessary to his research.

Unclear are the terms under which students and others participated in the diaries, whether student participation in monitoring was voluntary, part of a course, or otherwise, and whether waivers were obtain if any ethical exception applied.

It could be argued that a basic assumption about private life is violated by these various forms of monitoring. We expect that some places exist that privacy will be ensured, where only a known number of persons will be present, of a given category. Here, presumably, the individual can conduct himself in a manner that would discredit his standard poses were the facts known; and, of course, it is just these places that are the best ones to bug. — Erving Goffman

Free expression law protects Feagin and his publisher (Routledge) as fully as the subjects of his observation, regardless of the American Sociological Society’s guidelines. If the ethics of secret observation in academic research may not be clear, the power it wields is: “Any monitoring of any individual’s behavior that he does not know about will then have discrediting power. All forms of secret surveillance serve to undermine later activity, transforming it into discreditable performance,” Erving Goffman writes. Joe Feagin confirms, “Judging from the student diaries frequent repetition of racist stereotypes, jokes, languages and images is characteristic of many all-white gatherings.”

If secret monitoring is ethical and necessary for race scholarship, other races, and groups must be monitored and the results compared before recognizing Feagin’s work as social science.

An inquiry Routledge for this articled yielded that Tyler Bay was editor responsible for the book, and peer review was conducted by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Racism Pseudoscience

The nineteenth century biological race pseudoscience of Arthur de Gobineau and others is cited in abundance by race scholars, including by Philip Ewell. Joe Feagin states race science has been “resurrected” in the present time, singling out biologist and geneticist James Watson for his research on correlation between race and intelligence. Such scientists, Feagin writes, “speak or write as though there is no way to view data showing differential [sic] group scores on these conventional skills tests […] other than their negative framing of supposedly lower intelligence of certain people of color.”

The discredited race pseudoscience of the nineteenth century finds in Feagin’s work its antiracist inversion. These include lab experiments, for example, in which white persons are shown photos of black faces for “a few milliseconds.” Under a brain scan, “key areas of their brains designed to respond to perceived threat light up automatically.” Using medical technology to “prove” racism induces an illusion of scientific validity that convinces at least Feagin. As with secret monitoring however, his conclusion was determined at the outset and the experiment was designed to induce a specific outcome. Brain scans of other races must be similarly carried out, methodology made public, and results reproduced by others before any responsible conclusions may be drawn. It can be certain such work will not be undertaken since, as Feagin cites, biological race science is considered discredited and is certain to meet with poor reception. (In 2019, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory cut ties to James Watson, revoked his honorary titles, and called his work “reprehensible.” )

Feagin recounts even less rigorous psychological “test-studies” on white persons which border on voyeurism. He describes the need “probe deeply into the white mindset” in order “to understand better the way whites feel, think, act.” His anecdotal evidence includes quotations from black persons, such as “nervousness, body language, voice tones, the white eyes begin to follow you.” Feagin advocates experiments on children with the goal of producing in them more racial guilt. “Visceral white arrogance is part of her character structure,” Feagin writes, referring to a four-year-old.

Stressful Persuasion

Feagin lays forth a means to “eradicate” the white racial frame. This involves what he terms an “authentic liberty and justice frame.” “Authentic” liberty and justice contrasts to “white liberty and justice,” a self-framing in which white persons “assert themselves individually and collectively as ‘good’ people.” Feagin cites stereotypical statements such as “my family never owned any slaves,” “I’m not a racist,” and “I am a good white person.” White persons, he says, require virtuous self-framing to rationalize and interpret for themselves their own racism.

In a divergence from his mostly secular account of history, Feagin traces the origins of “authentic liberty and justice” to Christianity. This emerges late in the book, in a tone tentative and equivocal. Realizing surely that Christianity was a driving force in European imperialism, Feagin is quick to add that blacks created their own Christianity “counterframes” which, he says, offer justice and liberty that white frames have not.

Even after white individuals are convinced by rational arguments — “defeated intellectually” — the white racial frame persists in their minds emotionally. As a result, the “authentic liberty and justice frame” must be forced upon white persons using “pressures” and “small attacks from many directions.” Feagin proposes mandatory educational courses titled “Stereotyping 101” or “Racism 101.” It can take “many hours of instruction and dialog over many months” to get white persons to “even begin” to think seriously, “even for a short time,” towards deframing and reframing their views — that is, to bring them into alignment with Feagin’s. It is a “long and arduous process” that “requires much white effort and intention. White teachers must be “vigorously and constantly” educated by “critically foregrounding racist history.” Feagin proposes further experiments in lab settings that “induce” white persons to see complicity in the white racial frame by making them “review information” and “observe members of racially targeted groups in unstereotyped settings.” The deframing “must be clear and repeated“. Some people, “like women”, can use “borrowed approximations” from their own victimization but will be “still in need of more”, since the pressures required will extend beyond a “typical” white person’s racial comfort zone.

Feagin’s methods of eradication are consistent with a particular type of negative experience Erving Goffman calls “stressful persuasion.”

A practice in police interrogation, psychotherapy, and small group political indoctrination involves dwelling on what is normally unattended or undivulged, to the point at which the subject ‘loses control of the situation,’ control of information and relationships, becoming subject to self exposure and new relationship formation.

The public apologies described in the later Summer 2020 Timeline (Part 2) display this utterly defeated, confessional ethos, in which a subject is induced to “flood out” or “break frame,” accept voluntary public shame by detailing the wrongness of his or her words, actions and beliefs, apologize, and promise change.

It appears many individuals otherwise highly dedicated to their work and field, especially in the arts, can be induced not just to publicly profess, but also truly to capitulate in heart and mind to Critical Theory’s pressure. How and why does this happen?

Ideology

Joe Feagin’s primary error is failing to locate exactly the frame he is looking for: What he wishes to say is that all white people frame experience around racially white priorities, and that white people take this particular frame to be not a frame at all, but rather the ultimate, superior, and single way to define what is true and best. Ewell has a similar complaint: only white males have “been allowed” to determine what constitutes music theory. The first of the five main aspects of Ewell’s “Music Theory’s White Racial Frame” is: “The music and music theories of white persons represent the best, and in certain cases the only, framework for music theory.” This description is not of a frame, but of an ideology.

“Ideologie” originated in France during in the late 18th Century to refer to a “science of ideas.” In contemporary English use it appears often without clear definition or without distinction from “ideas,” and commonly carries a pejorative connotation.

In fact the word has an exact meaning. An ideology is a view or belief system claiming final and absolute word on what is true. In contrast to a frame, an ideology does not permit multiple interpretations of the same experience, but rather declares to them a single definitive meaning.

Ideologies are identifiable not by content but by form: a ideology posits that absolute truth can be attained or proven entirely on the basis of the ideology’s own premises, without reference to any external system. In political form, the premises for an ideology are usually an ultimate authority, such as a leader, state or party, or economic or political theory along with its author or authors. In other systems, premises may be axioms or observable conditions taken as obvious, unprovable, or not requiring proof.

The possibility of absolute truth, sometimes in the form of a system that proves itself, has occupied some of the greatest minds in philosophy, theology, logic, mathematics and science. Among these are Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Charles Sanders Peirce, John Stuart Mill, Noam Chomsky, David Hilbert, Bertrand Russell, Alfred North Whitehead, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Alfred Tarski, Giuseppe Peano, Douglas Hofstadter, John von Neumann, Alan Turing, Leopold Löwenheim, Thoralf Skolem, and likely the most famous contributor to formal logic, Kurt Gödel. This enormous topic will be covered here only in summary: no system of reason, logic, mathematics,science or any other variety is currently known that can prove itself true. Past some point, any system must be verified with reference something other than itself. In turn, information verified from that system must reference another. Whether this process is infinite and absolute truth is ultimately unreachable, or whether some stage or “frame” can verify all information once and for all, is among the profound questions of sentient existence.

At the same time, to have a world picture that provides meaning and order in the absence of absolute certainty is a fundamental human need. All human experiences, including religious and materialistic or scientific views, depend on some measure of faith, assumption, or “best guess” about information humans cannot verify with absolute certainty.

A system that generally receives and responds to input or feedback from other systems is called an open system. Open systems adapt to, and self-correct from, external input and feedback. They tend to produce “emergent” knowledge and information — that is, their outcomes are not predictable from earlier states and are generally open-ended. For this reason, open systems require tolerance for incompleteness, imperfection and uncertainty.

That incompleteness, imperfection and uncertainty are not always easy to tolerate accounts in part for the appeal of ideologies, which are one example of closed systems. Ideologies appear to provide complete answers to fundamental problems that otherwise appear unbearable or unsolvable. However, since ideologies are not generally responsive to external feedback and self correct mainly from within, they tend to produce self-reinforcing content. Ultimately, closed systems may become preoccupied entirely with their own content such that they amplify it indefinitely, leading to disordered behavior and, in worst cases, runaway scenarios. The most destructive conflicts in world history to date, those of the twentieth century, are attributable to the runaway behavior of closed political, social, economic, and, in the case of nuclear holocaust, scientific and atomic, systems.

If the “white racial frame” is in fact an ideology, then it would seem that antiracist and antisexist policies as informed by Critical Theory comprise the ultimate antidote: an open system, obviating all risk of ideology by ensuring diversity of viewpoints up to and including all citizens of humanity.

But this is not the case. The worldview Critical Theory offers is contingent upon accepting its system of language and belief. Here, reference to an absolute authority is necessary.

The Authority of Lived Experience

Aspects of both open and closed systems can indeed be oppressive to individuals and groups along many dimensions, not only by race, gender or identity. The potential for erratic and disordered behavior in systems, including human ones, can be and has been objectively identified and researched voluminously. However, Critical Theory is not reliant on this type of research or verification. Critical Theory relies rather on what is termed “authority of experience” to establish pervasive systemic oppression.

“Lived experience” is not original to Critical Theory. Subjective experience as a source of primary or ultimate knowledge is traceable to existentialist philosophers such as Edmund Husserl and Marin Heidegger, among others. It acquired political meaning in the work of 20th Century Postcolonial scholars and found appropriation into Critical Theory primarily through feminist and intersectional scholarship, such as in the work of Patricia Hill Collins, who emphasized “authority of experience” in Black Feminist Thought (1990).

In Critical race, identity and intersectional Theory, “authority of experience” refers to knowledge as lived and reported by individual persons, along with the broader idea that knowledge is mostly local and subjective, rather than general and verifiable. Specifically, the knowledge of individuals who report experiencing oppression has special authority (power) that the experience of others does not.

Systemic oppression need not be denied in order to reject lived experience as the final authority on it. The problem with an ideology is not related to its content, but to the means of establishing its content. Within Critical Theory, individual truth claims regarding systemic oppression are final and absolute; individuals do not experience systemic oppression because it is real, rather systemic oppression is real on the authority of lived experience. Critical Theory posits that knowledge about this oppression is out of reach to non-oppressed persons and that therefore only oppressed persons “are allowed to define” what constitutes systemic oppression. Sometimes, as in Joe Feagin’s experiments described above, “authority of experience” is collected and presented in statistical or other scientific-looking form to cause it to appear general and verifiable.

Once the locus of authority in oppressed individuals is established, further claims are made that may or may not be deduced from lived experience but are nevertheless authoritative on the basis of oppressed peoples’ subjective belief, or else, as in the case of Joe Feagin, others speaking for them. Many are not difficult to accept since they are historic realities: the violence of slavery that persisted as abusive and destructive patterns for many generations, official racist laws and policies that led to economic, social and political disadvantages across many dimensions including race and gender, and that people affected by these specific realities struggle in ways not familiar to those who do not.

However, there is some point past which the experience claimed by the oppressed cannot be believed simultaneously with the experience of those it is intended to persuade, or reconciled with information verifiable beyond reasonable doubt. Examples include Ewell’s claim that there were “another thousand” writers equal to Shakespeare, Feagin’s that white persons as a group have frames embedded in their neuronal structure, or that numerous undiscovered, or newly discovered, black or female composers were or are equal to Beethoven or Brahms in the context of the classical canon, that a piano proficiency or German language requirement is oppressive in the context of a professional music training, and so on.

An ideology’s ultimate authority, in this case the “authority of lived experience,” must always be correct. When something threatens the correctness of the basic authority, or any basic premise, the contradiction must be reconciled somehow. This occurs with reference only to content inside the ideology. When such claims fail to persuade, as Philip Ewell demonstrates, their truth must be forced using threats — that is, by imposing language and belief that override individual thought and compel compliance. When this fails, many ideologies simply remove dissenting members.

“Contextualization” and Narrative Control Power

Joe Feagin’s The White Racial Frame is best read as both history and example of the theory-praxis loop applied to the problem of racism. In particular, Feagin’s history of slavery is selective, and at times neglectful, towards many humanitarian topics of both the past and the present.

Critical Race Theory is concerned mostly with relatively recent American history. The United States faces a unique charge from race scholars. Feagin writes that the United States is “the only country to be founded on systemic racism.” This is a knowledge power claim whose potency depends on an unawareness of history outside of or before the United States, causing the general belief that slavery and racial discrimination are uniquely or especially American aberrations.

That is not the case however. Within Even slavery’s selectivity along the racial dimension is relatively recent. Slavs, Jews, Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Muslims, Greeks, Romans, Europeans, Native Americans, and many other peoples, including children of these, experienced enslavement at times throughout recorded history. Africa, the last be colonized by Europeans, offered by that time the advantage of a slave commerce that had existed on the continent since roughly the 7th century, as Africans rulers commanded the entrapment and sale of members of other black races to an international market that included the Islamic World, the Middle East, Persia, and the Ottoman Empire. The colonies that became the United States did not witness or commit anything near the worst of the horrors. Of the ten to twelve million transported in the Atlantic slave trade, Brazil was destination for the largest number, with most of the rest brought to other regions of South America or the East Indies. The United States was destination to 300,000 to 400,000 slaves, or roughly four percent, of the total.

What is perhaps most callous about Critical Race Theory in the context of world history is its near total silence on contemporary slavery. Slavery and forced labor remain on the African continent and other parts of the world at present, with most estimates being around ten million, or roughly equivalent to the size of the entire Atlantic slave trade population over the four centuries it existed. The discrepancy is, to my knowledge, unaccounted for within American Critical Race Theory literature. Those colonies who committed similar or worse atrocities, but did not become world superpowers, are all but forgotten in American race scholarship. Scholars such as Philip Ewell and Joe Feagin are meticulous in omitting this context.

“Contextualization,” of which race scholars are so fond, is thus an euphemism for selectivity. Scholars such as Feagin and Ewell select the contexts that support their particular views, omitting the ones that do not. If all histories are selective, and white histories selective according to white priorities, as antiracists claim, then contextualization in this redefined sense warrants no special consideration and is merely reinstantiates the problem.

Exclusive Inclusivity

Antiracism faces an apparent problem that its objective is to dismantle white male framed systems and reimagine them in the vision of radical inclusivity. The apparent “flaw” is that, in addition to resisting coercion, many individuals, not only whites or males, do not wish to be included in this reframing. That Critical Theory inspires dissent inherently frustrates its objectives and appears at first irreconcilable. Total inclusivity cannot be achieved when some people will not cooperate. In a virtual lecture, Philip Ewell remarks casually, “not everyone is going to get onboard, and that’s okay.”

How is that “okay”? The intricate solution has several historical precursors and can be glimpsed in the finale of the Ninth Symphony of none other than Philip Ewell’s “fine composer,” the above-average Beethoven. The text, “An die Freude” (Ode To Joy) by the German poet Friedrich Schiller, along with Beethoven’s choral setting, has figured in popular imagination and many historic events as an anthem for universal brotherhood and unity. It was adopted as the “Anthem of Europe” in 1972 and later by the European Union.

Somehow, the second strophe usually goes unnoticed:

Wem der große Wurf gelungen

Eines Freundes Freund zu sein;

Wer ein holdes Weib errungen

Mische seinen Jubel ein!

Ja, wer auch nur eine Seele

Sein nennt auf dem Erdenrund!

Und wer’s nie gekonnt, der stehle

Weinend sich aus diesem Bund!

Whoever has achieved the height

To be a friend to a friend,

Who has won a lovely wife,

Let him add his joy to our jubilation!

Yes, whoever can name even one soul

His own in all the world!

And whoever has never done so, let him steal

Weeping away from this bond.

Besides that “brotherhood” excludes non-males, the man who has not won a lovely woman, has never been a friend to a friend, or cannot name at least one soul his own, is sent away weeping. All humanity are united in a joyful bond, except some: the not-already joyful[1]I credit Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek with raising the question of exclusion in “Ode To Joy”..

“I view white persons to be extremely important to the process of reimagining our American music curricula,” Ewell likes to state, as though to invite everyone. But like the joyful bond of brotherhood in Schiller’s poem, inclusion in Critical Theory’s worldview is contingent. To be included it is necessary first to be “inclusive.” Here hides another redefinition: “inclusive” means “antiracist.” When an antiracist attitude is not offered voluntarily, it is coerced to make inclusion possible.

But what happens when even coercion fails? Recall that the ideology must never be wrong. The solution is to preserve the “inclusive” (antiracist) environment by liquidating any view that threatens it. “Inclusion” thus has another redefinition: threat of exclusion. So while exclusion itself is not a value of antiracism, the threat of it is. The assumption is that real exclusion will never be necessary, since everyone will eventually be persuaded, or else will die out. Declaring total success is postponed indefinitely until that occurs. “It is very difficult for white males to see their own entitlement,” Philip Ewell says. Ultimately there is no allowance for disagreement, only for “difficulty”. There are only three options: agree now, agree later, or be excluded to preserve inclusivity.

Those who do not ultimately submit are referred to as “white supremacists.” Recall from Part 4 that this term has antiracist redefinition: it refers to a person who does not believe or agree with the premises of antiracism. Although unintelligible from outside the ideology, this closed logic preserves the absolute truth for those who remain inside it, and the flaw is accounted for. The illusion of success is achieved by referring to exclusion as “inclusion.”

Like the need for a stable worldview, the human need for belonging and the fear of ostracism are primal. Threat of expulsion from any society, academic, professional, or personal, is a powerful motivator to feign or achieve agreement with antiracism.

The question remains where dissenters should migrate, assuming they are to remain employed or at least somehow engaged in their profession or in society. Recall, Philip Ewell points out, that these are not always the “senior white male colleagues”, but may be any person of any race or gender, whether or not they make their thoughts or emotions known. What happens, for example, to the “sixty-plus crowd,” or others overlooked by Ewell’s “statistics”?

All the above may be viewed in terms of the three predecessors to antiracism Philip Ewell finds problematic by degrees: segregation, integration, and assimilation. Those who cannot assimilate to antiracism may become “allies in name only,” declaring agreement while thinking or feeling some other way, and thereby at least achieve integration. Those who cannot or will not do so must accept segregation until they can, or as the final option.

Schiller later called the poem a “failure.”

Communication, Metacommunication and Frame Entrapment

At this point it is proposed to anyone who has read this far to to discard all previous lines of thought and re-assess the anatomy of the problem from the beginning. What we have here is a not a question of music, race, or gender, but a general breakdown in communication.

The problem concerns not the content, but the kind of communication. A rigorous means to analyze it developed at the Palo Alto Mental Research Institute (MRI), which was established in 1958 to apply systems theory to the study of family dynamics, communication and psychotherapy. The MRI consolidated knowledge from several fields, among them cybernetics, which studies input, feedback and causality in circular systems and processes. The Palo Alto Group was also informed by psychiatrists and scientists including Sigmund Freud, Milton Erickson, J.L. Austin, Norbert Wiener, and Gregory Bateson.

A primary focus of the Palo Alto Group was on metacommunication, or communication about communication. The Palo Alto Group originated the idea that communication involves both a content and a relationship aspect. The content aspect is the message being exchanged. The relationship aspect is metadata about the kind of communication taking place, designated in behavior, tone, implication, or more generally the context or relationship of those communicating.

Though the relationship aspect is not explicitly stated, it is often namable. When children tease, for example, insults, threats and physical behaviors are not interpreted as actually insulting or threatening, since there is a nonverbal metacommunicative agreement “this is play.” When the relationship aspect designates equal status, as here, it is called “symmetrical.” When the relationship aspect designates differing power or status, but the communicators still agree upon it, it is called “complementary.” Between parent and child, for example, the relationship aspect designates from the parent “I take care of you” or “you must obey,” while from the child, it may designate “I am dependent on you” or “I understand the rules.” The relationship aspect is learned over time as a part of total communication, like language, and does not arise always with purposeful intent or awareness.

When the relationship aspect is neither symmetrical nor complementary — when there is conflict or uncertainty about the relationship aspect — communication becomes confusing, dysfunctional, or disordered. The audience to Philip Ewell’s 2019 plenary talk perceived the relationship aspect to designate “this is scholarship,” “we are music theory colleagues,” and “this is material for intellectual debate.” The Journal of Schenkerian Studies contributors did so with especial naivete. But the relationship aspect of Ewell’s talk designated “I speak from authority,” “music theory is white and exclusionary,” and “to deny this is to be a white supremacist.” The relationship aspect actually appears as content in Ewell’s paper: “the Enlightenment subsumed racist ideas under the rubric of humanistic discourse, another instance of white racial framing.” Here the relationship aspect designates “no humanistic discourse is permitted,” and “to debate me perpetuates music theory’s white racial frame.”

When the relationship aspect is in conflict, a solution is to bring the relationship aspect into discussion as content — to metacommunicate. But Critical Theory makes metacommunication unachievable. Attempts to name or discuss the relationship aspect are interpreted rather as content. That white or other persons would deny acting from the “white racial frame” is anticipated as one of its features. Resistance is thus accounted for. The result is what Erving Goffman calls “frame entrapment.” Frame entrapment is a psychological dilemma in which no way to escape a frame is available, since any attempt to do so reinforces it.

The world can be arranged (whether by intent or default) so that incorrect views, however induced, are confirmed by each bit of new evidence or each effort to correct matters, so that, indeed, the individual finds that he is trapped and nothing can get through.

Transforming remonstrances into symptoms; The character we impute to another allows us to discount … transforming into “what can only be expected”. Thus are interpretive vocabularies self-sealing. […] In these cases, truly, we deal with the myth of the girl who spoke toads: every account releases a further example of what it tries to explain away.

Once frame entrapment is accomplished, the contained has no way out. To instigate debate becomes a strategy for the framer to bait the contained into further statements from within the frame.

If frame entrapment is visible in Philip Ewell’s work, Joe Feagin lays it bare as a means of psychological coercion. Even white antiracists, Feagin says, “assume their goodness”, and in doing so, “create problems” for racial justice. Submitting to antiracism, then, if not in exactly the correct way, also “proves” the white racial frame.

A powerful outcome of frame entrapment is that, where formerly only the special claims of the ideology were doubted, broader reality and personal belief may become more generally vulnerable to doubt. Here the private terror that Critical Theory evokes can be precisely located: when coercive authority induces the mind to doubt perception and reality. The fear in the eyes of Ewell’s “deer in headlights” colleagues is existential: parameters are changed so suddenly and fully as to impute most or all accumulated professional knowledge as central to a narrative of moral shame.

To doubt one’s own perception or reality, or even to perform doing so, may be so disorienting that it undermines personal agency so near total submission may be elicited with enough pressure. As Goffman writes, the coerced is “subject to self exposure and new relationship formation.” The subject is then vulnerable to almost any explanation that resolves the confusion. At this moment, antiracism offers the explanation that the subject is beginning to “see their own entitlement”, recognize “the white racial frame”, and starting the process of self-reflection. Once this explanation is accepted, to go back is actually quite difficult. The outcomes differ only by degrees with the transgressive psychological tactics used to break resistance in any authoritarian system.

The relational aspect of communication in Critical Theory thus parallels the content aspect. Confusion obfuscates meaning and makes dissent impossible except as evidence. Attempts to either metacommunicate or to produce new or different content, no matter how clever, are powerless to alter outcomes.

With these facts clear, an unqualified conclusion of this article is that the possibility for reason or argument to have any effect in opposition to Critical Theory is rejected finally. No further advice on it can be offered. Those invested in de-escalating Critical Theory’s effects must turn attention instead to this reformulation of the problem: disordered communication.

Gregory Bateson and the Double Bind

In his section on frame entrapment, Erving Goffman refers again to the originator of framing, Gregory Bateson. Bateson was an anthropologist and psychiatrist whose transdisciplinary work defies category and summary. Two books and a body of shorter publications, research documents and personal letters have influenced cognitive science, communication theory, sociology, game theory, computational science, ecology, political systems, cybernetics, and systems theory. Bateson was critical of the “theory-praxis loop” described earlier, and of what he called “purpose-driven” work, by which he meant the expedient solution to a particular problem while missing its attendant systems. As a result, his writing is throughout cautious and open-ended, reluctant to advance final conclusions.

At the Mental Research Institute in Palo Alto, Bateson developed and tested a hypothesis on the cause of schizophrenic and other disordered behaviors within families, which he termed the double bind. Switching fields and posts over several decades, he continued developing the hypothesis through study of animal communication, ecology, and political and social systems.

The double bind is a special type of dysfunction at the metacommunicative level. It is best understood in its original context, the family. It involves two or more people, usually a parent and a child. There is a primary verbal instruction, such as “Do not do X”, on threat of negative consequences. A secondary instruction contradicts or impinges upon the child’s ability to comply with the first, also on threat of punishment, but expressed such that it cannot be named, by behavior, tone, or context. Finally, a third instruction or constraint prevents the child from escaping the situation in any way.

In childhood, Bateson remarks, the impossibility of “escaping the field” is nearly always assumed, since the child is dependent on parents. But double binds are not limited to children, and Bateson’s later formulations retain the more general constraint that “naming the problem is not permitted.” Through repeated experience, the double bind acquires familiarity such that “almost any part of a double bind sequence may then be sufficient to precipitate panic or rage.”

The double bind is not necessarily malicious, and roles are not always clearly divided into victim and abuser. Rather, the double bind is a total system in which the apparent abuser and victim both participate. Bateson writes, “the statements which show that a patient is disoriented can be interpreted as ways of defending himself against the situation he is in.” As it is part of a general communication vocabulary, the double bind can be learned and passed to others through families and other systems.

The double bind might seem fertile material for misappropriation into Critical Theory, since it appears to map readily onto the subjective experience of oppressed persons. Bateson’s language even bears some similarity to Philip Ewell’s aversion to “solutionism.” Systemic oppression can in fact be demonstrated and defended using systems theory and the double bind. But Bateson’s name is scarcely to be found in Critical Theory literature.

Possibly, that is because the double bind corresponds with striking precision to the threats, contradictory meanings, and frame traps that Critical Theory uses to confuse and destabilize. Double binds abound in Critical Theory’s communication patterns and the reader may now amuse herself or himself by rereading this article and locating them nearly everywhere. For example, the primary instruction “have an honest discussions on race” on threat of being seen “unwilling to have an honest discussion on race” (from Ewell’s 2019 plenary paper) coexists with the secondary, nonverbal instruction for the outcome to be agreement with antiracism, on threat of being called white supremacist. Many individuals cannot be honest and agree with antiracism simultaneously. There is no way to name the problem, since doing so reveals disagreement with antiracism, disobeying the secondary instruction and leading to the same penalty. If the individual resolves the dilemma by expressing false agreement, he or she disobeys the primary instruction to be “honest” and risks discovery, with the same negative consequences.

Double binds reduce trust and increase disorganized thoughts and behavior. No matter what the individual does, they are wrong in one way or another, since any response leads to negative consequences. Ultimately, a double-binded individual may develop paranoia that everyone else is in agreement, that only he or she has misunderstood in secret isolation. In turn, the range of possible behaviors is reduced, and coercive positions become more likely to produce asymmetrical but complementary submissive ones. Finally, the coerced learn the communication pattern and utilize it themselves. In cybernetics this is known as “runaway” and is a means by which large populations can come under the spell of ideologies.

With all of this understood, it becomes clear antiracists and other supporters of Critical Theory are also double binded. For example, the primary instruction “include everyone” on threat of failing to be antiracist coexists with the secondary reality that this not possible, as described earlier. To name the problem is to state a flaw in the ideology, which is not permitted. The best option remaining is to redefine the words in the instructions and adopt the closed logic of the system, as described earlier. Persons who support Critical Theory are no less in the grip of the double bind than opponents; in many cases opposition is where they began.

Frame Trapping Critical Theory

Critical Critical Theory Theory demonstrates that Critical Theory, like the system of white interests it critiques, has interests of its own. Academic Critical Race Theorists are concerned with exactly those aspects they condemn in most whites: their own power and interest. In most cases, professional academics are so removed from the hardest economic and social realities afflicting underprivileged races and classes that their primary concern may be inferred more simply: it is likely their own professional notoriety in the field of Critical Theory. Once this is clear, Philip Ewell’s and Joe Feagin’s claims become more intelligible: Feagin and Ewell are professional academics working in their own professional interests: to gain recognition, notoriety, power and influence both in and out of academia. This, and not their claims about society in general or music theory in particular, furnishes the most convincing explanation as to their motivation both to believe and to propagate their ideas.

Once the scale of appropriation from Western thinkers is understood, it is clear the “white racial frame” is both fragile and self problematizing. As the many examples in this section illustrate, Western thought is inherently self critical to the extent that to critique it almost invariably entails participating in it. Philip Ewell correctly points out that even the idea of the West is Western, while overlooking that the most virulent critiques of it are also Western. To these, American Critical Theory has contributed nothing new. It is not in fact necessary to view Critical Theory or its antecedents as “white” or “male.” Critical Theorists use this knowledge for the same reason others do: it is useful and powerful. Not to acknowledge or cite its origins alters that in no way.

Critical Theory may then be treated as it treats any other problematic worldview, by subsuming it within a posited frame: it could be called “Critical Theory’s Frame Entrapment Frame.” Its claims may then be discharged similarly, by using content as evidence to problematize the frame. To recognize the power frame traps and double binds brings the relationship aspect of communication with Critical Theory, if not into complementarity, at least into symmetry. The outcome is an adversarial relationship, a situation to be discussed in Part 6.

Correctives

What do these realizations make possible?

Critical Critical Theory Theory is at once serious and absurd. A new theory might in turn deconstruct its mechanisms: Critical Critical Critical Theory Theory Theory.

But to answer theory with more theory is to participate in the theory-praxis loop that generated flawed theory in the first place. In “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame,” Philip Ewell writes, “a rush toward solutions, our [sic] ‘solutionism’ […] is part of the problem of our white racial frame. […] Of course we should seek solutions to the problems created by our racialized structures, but we must also reframe how we understand race in music theory, which we cannot do if we rush to find solutions to problems we do not yet understand or even acknowledge.”

With quite different intent, but in striking parallel, Gregory Bateson writes, “Innovations become irreversibly adopted into the on-going system without being tested for long-time viability; and necessary changes are resisted by the core of conservative individuals without any assurance that these particular changes are the ones to resist.”

Correctives on a scale beyond the individual are offered in the sixth and final section of this article, forthcoming. In the meantime, it is suggested to heed the unpredictability of the theory-praxis loop, as proposed at the start of this fifth section. No special alchemy is actually needed to unravel the confusion. The apparent “riddle” Critical Theory presents — frame entrapment, double bind communication patterns, redefinitions, and so on — already have solutions. More cannot be wished than to double down on the history of these ideas to the fullest depth possible. Toward this end, related works are listed below, including many titles that informed this article.

Recommended Reading

Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason (1781) Among the first modern philosophical works to question whether absolute knowledge is possible, and to propose that the mind and the self shape reality. Usually considered the start of “German Idealism”